Jumping into the open ocean at night certainly isn’t for everyone. Just the mere thought of diving in the dark can sometimes create a bit of anxiety with some divers, adding in the extra dimension of diving in the open ocean at night and it positively spooks them.

Black water diving is not your typical night dive and we’re not heading to the bottom to explore the sand. In fact, the bottom is the last place you would want to find yourself on an open ocean dive like this, exploring however is what Black Water diving is all about.

Black Water diving is an advanced style of diving that is done well offshore, over deep water and away from any structure, out in the void. The target subjects are planktons and their predators.

Each evening at sunset, this planet’s largest animal migration begins, as planktonic life forms move up from the depths to disperse and feed. This vertical migration carries with it many incredible ocean oddities that would never be seen on a typically regular night dive.

By inserting ourselves directly into this food chain, plus a little luck, we might be able to see some of this action and hopefully capture a few unique images. Vertical migration is one of the buzz words enthusiasts of black water diving will use to describe the upwards movement of planktons from the depths to-wards the surface.

Getting ready for night dive

Black water diving has recently taken the underwater photography community by storm, with building enthusiasm that is palpable. The experience is un-matched by any other and offers unique photo opportunities that have been highly placed in nearly every competition they have been entered. Many long established competitions have now introduced Black Water as a category. It’s become highly competitive.

It takes a bit of practice and requires a little dedication. Late nights are the norm, so resting-up during the daylight hours becomes a part of the routine. A skill that must be learned is how to hunt for subjects while drifting in the darkness with nothing more then a torch to light your way. After a few such dives, it comes together and the whole routine eventually becomes second nature. You may lose interest in regular day dives, but everything, including the computer you use, will be need to be adapted for use in the dark.

Methodology for Setting Up.

Shooting in the open ocean on a regular dive is not the same as black water diving. There are two basic methods to getting good results.

The Down-Line Method from a Boat:

Over time we’ve developed a rather extravagant set-up with a down -line that offers a great visual reference, both above and below the water line. Our down-line has a lit orange buoy at the top of a 33-metre weighted rope. The rope has several high powered lights attached to it, and these attract the plankton and gives a good visual reference that allows divers to free swim at any chosen depth, without being tethered.

Over time we’ve developed a rather extravagant set-up with a down -line that offers a great visual reference, both above and below the water line. Our down-line has a lit orange buoy at the top of a 33-metre weighted rope. The rope has several high powered lights attached to it, and these attract the plankton and gives a good visual reference that allows divers to free swim at any chosen depth, without being tethered.

The Bonfire Method from a Boat or Shore:

This alternative method can be effective but, depending on the subjects your shooting, can be very productive or a not at all.

Secure the lights on the bottom (or just off the bottom) with their beams facing up and towards deep water. Alternatively, drop a line from the anchored boat with lights attached. Experiment and try both and see what suits you best. Don’t discount this method as being second best. It’s just another way of seeing inshore larval subjects and can create great photo opportunities.

Secure the lights on the bottom (or just off the bottom) with their beams facing up and towards deep water. Alternatively, drop a line from the anchored boat with lights attached. Experiment and try both and see what suits you best. Don’t discount this method as being second best. It’s just another way of seeing inshore larval subjects and can create great photo opportunities.

Basic Tips for Black Water Photography

Dive skills - Safety first always for diving in the dark. Be sure to have great buoyancy control before venturing out. During the dive, move slowly and try not to fin too much as this can create a pressure wave. Each movement causes turbulence and many of the delicate creatures could be destroyed outright by it, or sent spinning away, curl up or dash off.

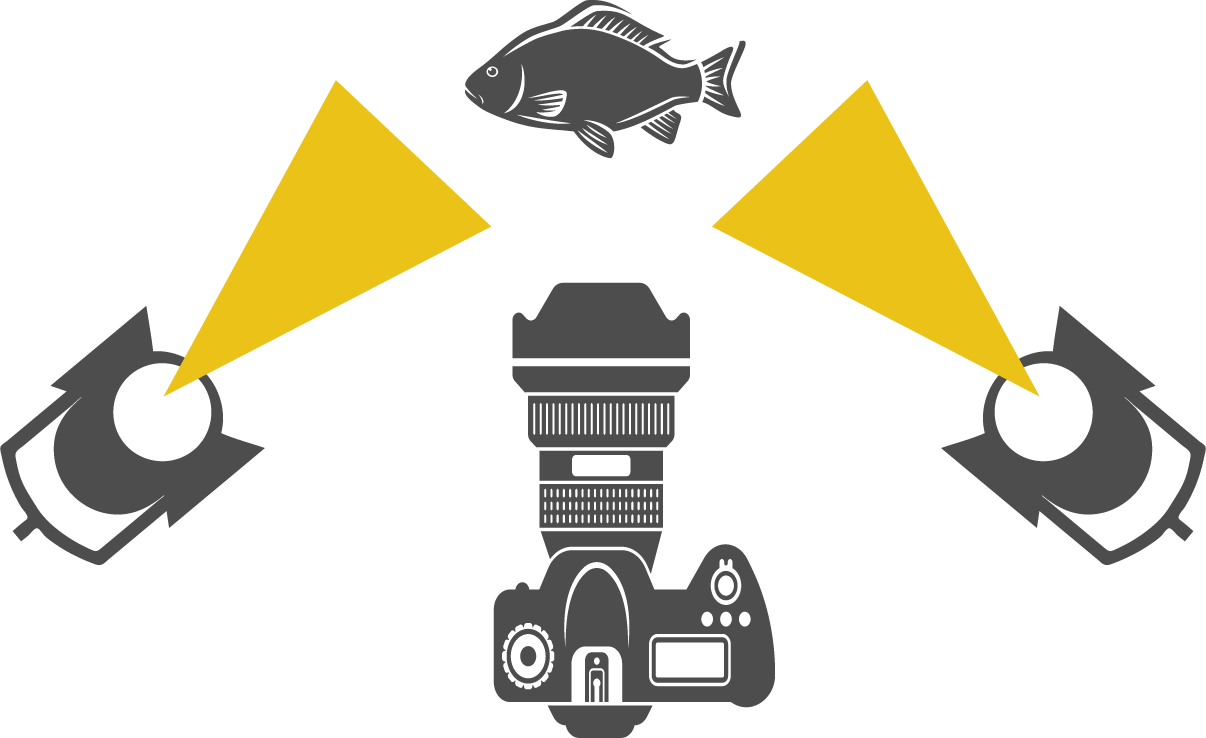

Photo skills - Much of what will be seen is very small. Use a 60mm macro lens on an APSC or full-frame camera, if possible, and without diopters. Float arms keep your rig easy to handle underwater and a clip to secure your camera to your BC is a good idea, just in case you need both hands. Using a wide-beam focus light trained over your lens port enables you to focus fast. Positioning strobes well away from the lens axis, angled inwards, will help to eliminate backscatter in the recorded image.

The Hunt - Searching for subjects in the water column during a dive is a skill that most of us don’t have to start with, but soon develop. A handheld torch with a narrow penetrative beam will let you search farther even if the water is turbid.

Camera Settings

With a full-frame or APSC, camera I prefer to shoot at a higher ISO (such as 400) and smaller f/stop’s (larger f/number – f/22) to gain batter depth of field on the subjects. If my subject is reflective, I’ll roll the f-stop up to an even higher number (f/32). This helps to bring the exposures back to where I prefer and if I need more light, I’ll open the lens wider (e.g. f/16). Unlike standard macro shooting, depth of field isn’t as much of a worry as is overexposures. Don’t get too hung up on the aperture settings, just use it like a dimmer switch. Using as fast a shutter-speed (1/200) as your camera will allow for perfect flash synchronization will eliminate the effect of the focus light in the picture. Compact cameras cannot shut the lens down a tightly as a DSLR and the smallest f/stop is often as wide as f/5. You need to use a much faster shutter-speed in conjunction with that, to get the same effect.

Your camera will be able to pick up the little details and colorations that will only be revealed in post-production on your computer, so exposures are every-thing.

Backscatter is often inevitable. Use the following tips to help reduce backscatter.

Strobe Angles.

Once underwater, approach the down-line and take a few images of the line it-self from an arms length distance to judge the light quality and adjust camera settings. Strobe’s angled inwards and adjacent to the lens port is a good starting point.

For larger subjects or for subjects farther from the lens port, position the strobes well away from the camera’s lens axis to spread the beam.

.jpg)

It’s not always the shooter that gets excited on black water dives. So can the subjects. Many of the subjects will swim straight at the lens, pausing just long enough for you to capture an image. Shooting at a smaller f/stop (higher number) will help to knock down the reflectivity of your subject and allow for more control over your exposures, revealing the colorful details.

.jpg)

The nautilus is a subject that is now highly prized. The female builds her shell to rear her eggs. She can be robust in size, quite fast and will certainly have you finning like crazy. These argonauts are often times seen clinging on to ob-jects such as jellyfish, that they can use as a food source and perhaps for protection.

.jpg)

Planktonic flounders and flatfish come on a plethora of styles and varieties. Most are as small as your thumbnail. This one was palm-sized and ready to settle on the sand very soon. However if you look closely, you’ll see the eyes are still on either side of its head.

(1).jpg)

At the surface or just below the surface is also a great place to hunt for sub-jects like this colorful flying fish. Watching for the reflection and trying to cap-ture that as well, adds another dimension to the image.

.jpg)

Capturing behavior is a given on these dives so be prepared. Pelagic squid are super-fast and hunt in packs. Inking to stun their prey, they snatch their victims up in a flash.

.jpg)

A gelatinous predator, the night sea is full of small mollusks, interesting worms, small shrimps and of course the things that feed on them. The Hetero-pod is a single winged mollusk and a voracious carnivore that feed on smaller subjects like, Pteropods, another type of mollusk that has two wings.

.jpg)

The immortal jellyfish can live forever, reverting back to the polyp stage when stressed or after it has reproduced. Very small, measuring approx. 2-4mm at the bell, it can extend its network of lacy tentacles when hunting, so it appears much larger than it really is. They are difficult to photograph well, as they are a quite sensitive to light. Gaining sharp focus can be difficult, so it’s a good idea to pre-focus on your hand, before moving into the subject without the focus light turned on.

Many subjects drift in a static position but will begin to rotate if lit for an extended period of time or if you make quick hand/fin movements.

I find some jellyfish easier to expose at a lower aperture like f/14, be careful to readjust the strobe power setting as such subjects are also easy to overexpose.

Many subjects drift in a static position but will begin to rotate if lit for an extended period of time or if you make quick hand/fin movements.

I find some jellyfish easier to expose at a lower aperture like f/14, be careful to readjust the strobe power setting as such subjects are also easy to overexpose.

.jpg)

The jackfish and jellyfish together are a great photo opportunity. The symbiotic relationship between the two works well. This particular type of jellyfish has actually developed a small flap under the bell where the fish can hide or rest.

.jpg)

The wunderpuss, in the settling phase, is another show-stopper. Transparent and resembling a creature from a scifi movie, these small octopus are calm and photogenic. To capture movement, you must slow the shutter speed down and increase your focus light power. Then pan your camera while shooting. It takes a bite of practice but can result in some interesting images.

.jpg)

T.gracillis - the blanket octopus is legendary. They are known to rip the tenta-cles from jellyfish and (it’s presumed) to use them as a defensive tool or for hunting. The female can become huge, measuring in several meters, yet the male remains small, measured in only centimeters. When the wings of the female are fully extended, it appears like an octopus in a squirrel suit. The blanket can be deployed and retracted very quickly, which ads to the difficulty in photographing them well.

Black water photography offers a bounty of new and unique subject for the adventurous underwater photographer. Concentrate on your dive skills and the rest will quickly fall into place as you gain a comfort level in the open ocean. Look for the small subjects first and if something a little larger appears, do your best to capture the action. Remember to save some air for the surface too; flying fish and other incredible larval fish are often founds in the upper few metres of water.

Please visit the Blackwater photo group on facebook for more images from around the world.